Big data is the backbone of modern particle physics. Did you know that CERN produces millions of gigabytes of data in an average experimental run? While CERN smashes highly energetic particle beams to produce a large number of collision events (and thus a large amount of data), dark matter searches are typically what are called “rare event searches” in the particle physics community. Rare event searches, as the name suggests, seek to find extremely rare physical phenomena in the universe, such as a dark matter particle scattering off a crystal in a deep underground laboratory. By definition, you would naturally expect less data from a rare event search experiment compared to a collider experiment such as the LHC. Yet, my experiment, SuperCDMS e.g., is expected to produce ~100 TB of data in a year. To provide a sense of how massive this is, the training data for GPT-3 was 570 GB post filtering of the acquired 45 TB of data from 2016-2019.

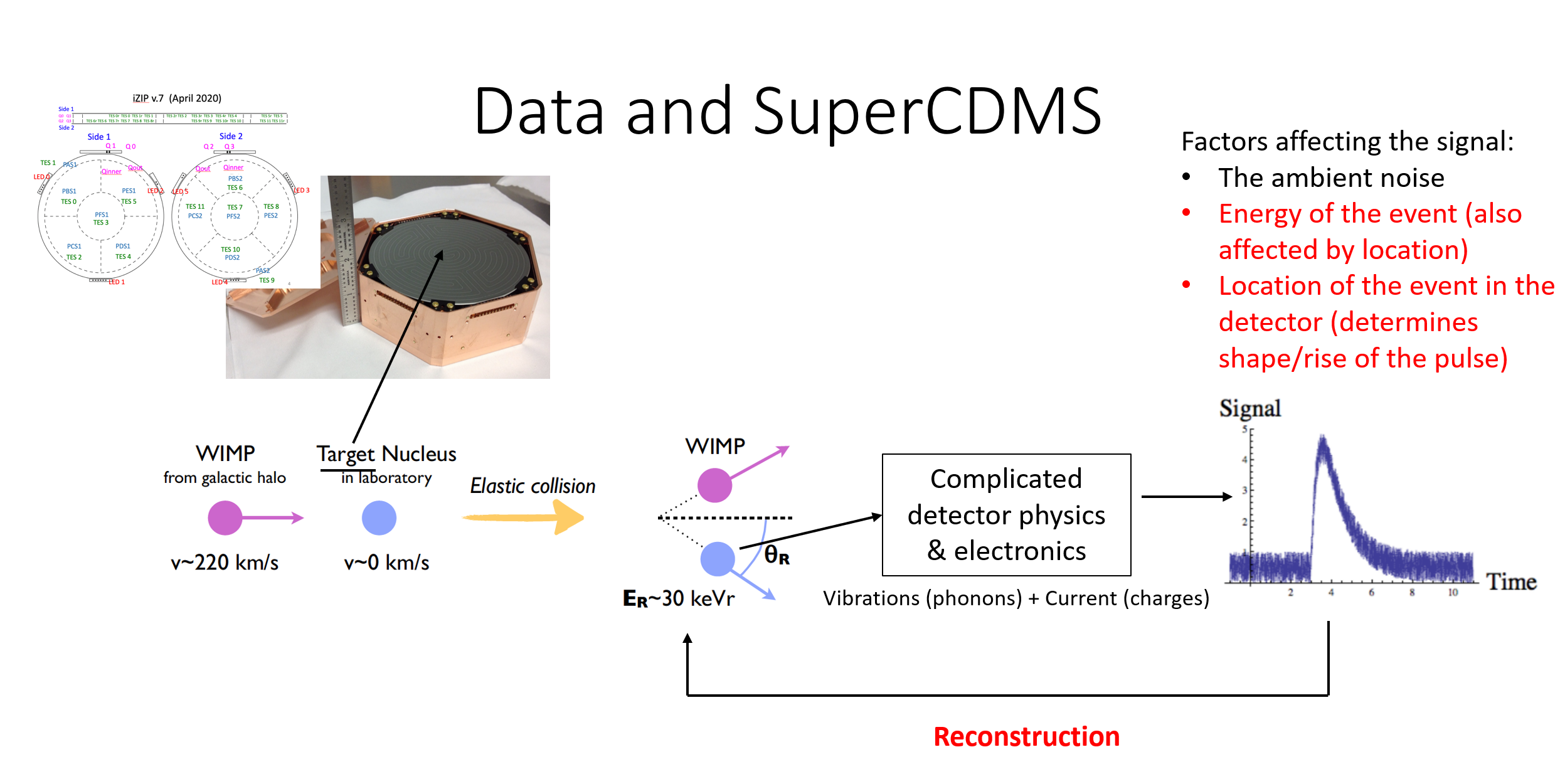

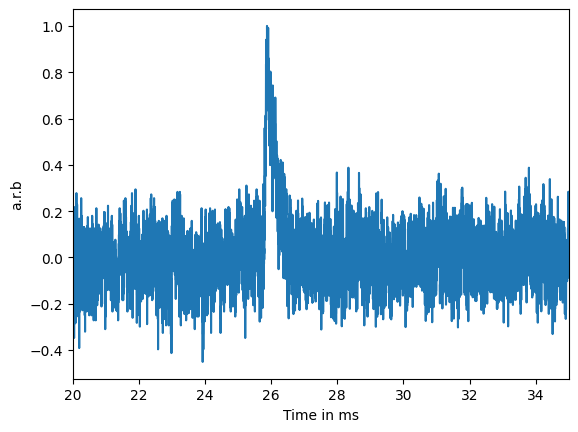

So what does our data look like? Our raw data acquired from the detectors looks are digitized waveforms sampled at 625 kHz rate, i.e., time series data. It could look like this:

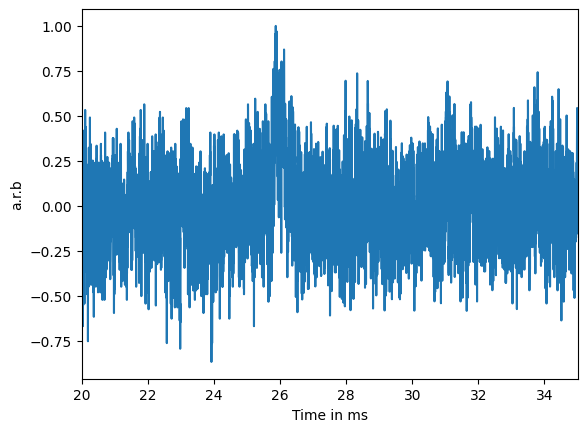

or, this:

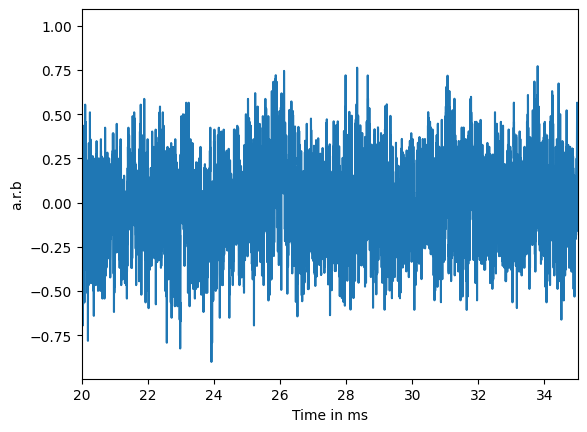

or even this:

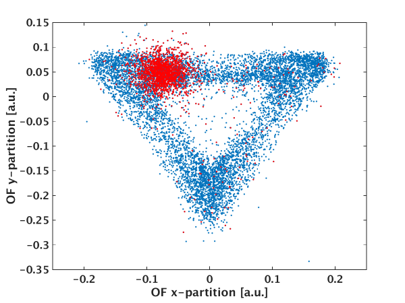

Can you spot the pulse in the last one? Regression, PCA and even classifiers with CNNs are approaches used to study data of this kind. We also often process these data sets to decompose it into physically interpretible and human analyzable components. Processing maps the raw pulses you saw above into a feature space. Reduced features (called reduced quantities in SuperCDMS) are, thus, another form of data we study. This could be the location of events clustered in a channel like this (image related to this paper):

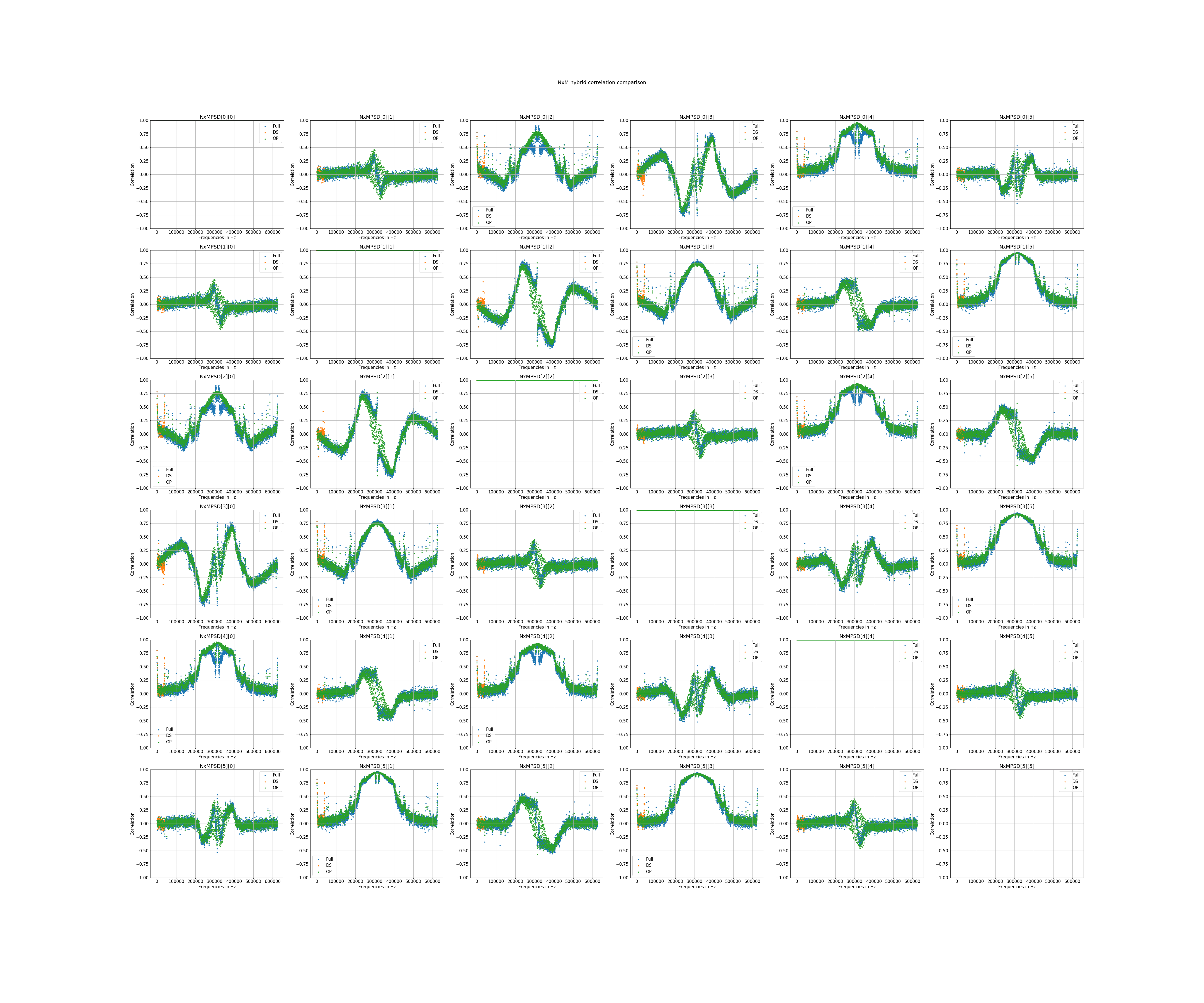

or the correlation between various detector channels like this:

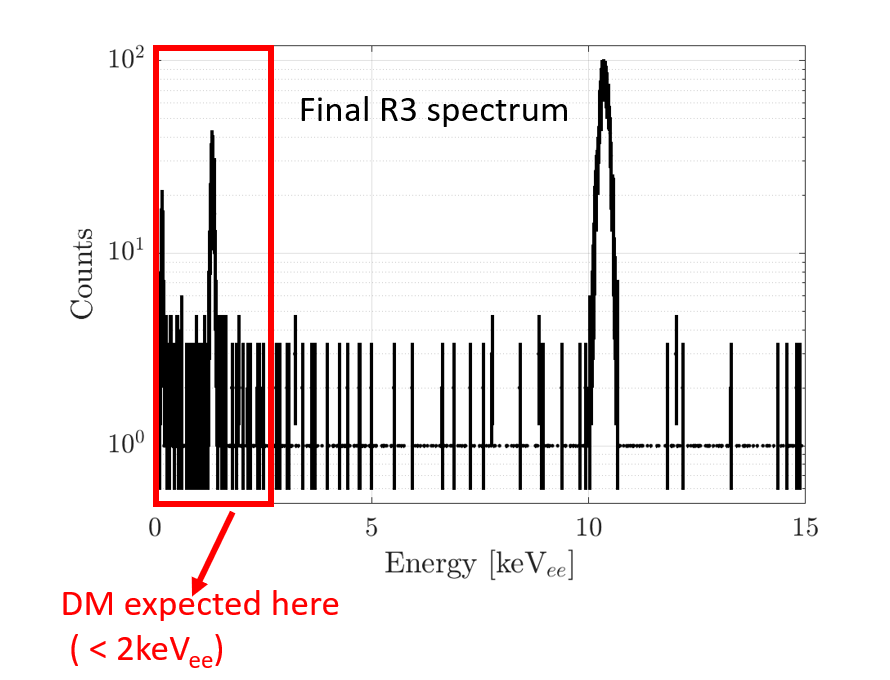

or the event energy distribution (image related to this paper for example) like this:

Big data calls for extensive and creative data analysis techniques, making every particle physicist also a data scientist.

Want to know how machine learning can help detect dark matter? Check out this project page