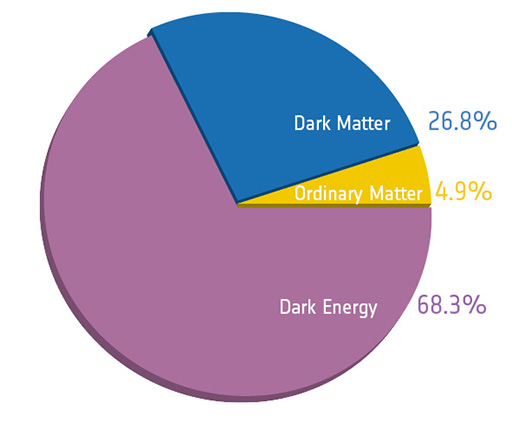

From the distant star light arriving from millions of light years away to the fundamental particles composing our surroundings, all encompass what we term “matter.” Every element of our existence, from ourselves to the world around us, is constituted of matter. By studying processes that happen in galaxies around us or by careful studies of the residual radiation from the early universe, we can estimate the total amount of matter in the universe. It turns out that the total matter content of the universe is much larger than what we can see around us (“visible matter”). In fact, visible matter constitutes only about 5% of the total matter content of the universe. About 70% of the universe is a form of cosmological constant, called dark energy, which is responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe and still a mystery. The remaining matter termed dark matter is a crucial component in the evolution of the early universe, shaping the large structures we see today.

Pie chart showing the contents of the universe. Image from this page

Pie chart showing the contents of the universe. Image from this page

The origin and nature of dark matter is one of the biggest unresolved mysteries of the universe. Many experiments have tried to find dark matter, but it remains elusive. We know that dark matter must have some mass and exert gravitational effects on visible matter. Dark matter, if it does interact with visible matter in some non-gravitational way, must do so very weakly. The Earth’s surface is bombarded by cosmic radiation which limits our ability to identify meaningful candidate signals above ground. Therefore, most dark matter experiments are performed in underground labs where the rock shields the detectors from radiation.

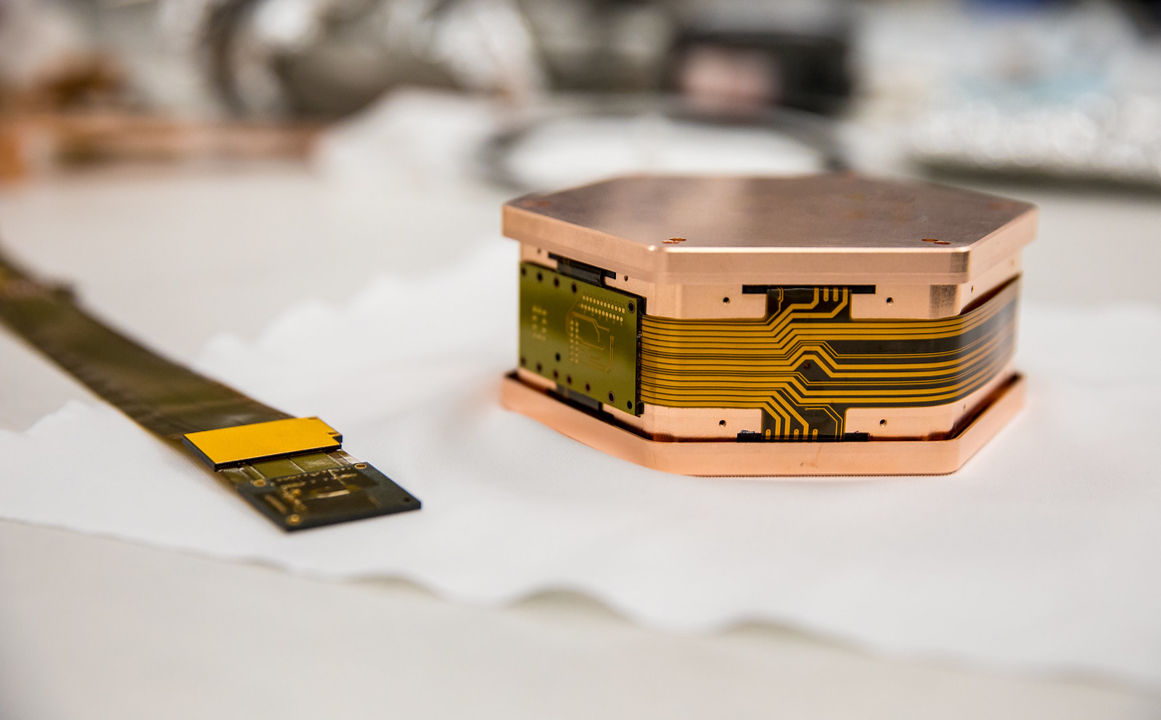

SuperCDMS is a direct dark matter search experiment which looks for a signal from a dark matter particle scattering off of cryogenic, superconducting detectors. The detectors are made of ultrapure Ge and Si crystals equipped with superconducting circuitry to read out waveforms (read more here). The scatter produces a recoiling nucleus or electron which in turn produces tiny vibrations and some charges in the crystal which are measured as a digitized waveform. The signals are analyzed like typical time series data using statistics and machine learning methods.The signals are also processed to extract meaningful features which are also analyzed meticulously. The energy transferred from the dark matter particle to the recoiling nucleus is obtained from the measured signal which can be used to trace back the mass and properties of the incoming particle. Watch this video to see a simulation of our experiment:

SuperCDMS detector

SuperCDMS detector

I’m involved in many aspects of the experiment - from characterizing new detectors and noise assessment to software development and data analysis.

Advancements in technology have not only enabled us to construct extremely sensitive detectors but also use the power of data science to extract the faintest signals from large, noisy, data sets. Dark matter experiments are often slow to adapt machine learning and AI primarily because of limited training data and the limited knowledge about what a dark matter signal even looks like. My research aims to address this gap by applying machine learning tools to improve the energy resolution of our detectors and thus our overall sensitivity to lighter dark matter particles. Over the course of my 5 years with SuperCDMS, I have pioneered novel methods, implemented code, and spearheaded significant projects within the collaboration. A key part of my research focussed on reconstructing an event or particle interaction from the acquired raw data, translating it into interpretable information to help identify signatures of dark matter. I have developed many novel reconstruction techniques leveraging advanced statistics and, more recently, machine learning methodologies such as Gradient Boosted Decision Trees and Principal Component Analysis. These efforts have yielded multiple reconstruction algorithms and techniques which have demonstrated the ability to enhance the overall sensitivity of the experiment. To read more about this, refer to this project page page.

I played a leading role in detector testing and pre-commissioning efforts at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) in 2022. SLAC is a surface facility where the exposure to cosmic radiation is large. These particles flood the detector with so many hits that the software systems cannot keep up. They also radiogenically activate certain isotopes in the detector material which can generate false signals. Therefore, for seamless detector testing, these detectors ought to be operated underground. Presently, I am spearheading the testing of six new detectors at SNOLAB. In this capacity, I am responsible for overseeing detector testing and data analysis efforts. Our primary objectives include detector characterization, calibration, and noise assessment.

I am a developer for MIDASDAQ, the in-house SuperCDMS Data AcQuisition (DAQ) software and the current release manager for SuperCDMS DAQ, the umbrella package which encompasses all DAQ sub repositories. I am also a developer for CDMSBats, the in-house package which processes raw data and extracts meaningful physical quantities from it. The above repositories are privately owned by SuperCDMS and therefore if you’re not a member of the SuperCDMS project on gitlab you cannot view them (even a fork). I’ve tried to produce a software profile to demonstrate my experience. I am happy to provide more information upon request.